|

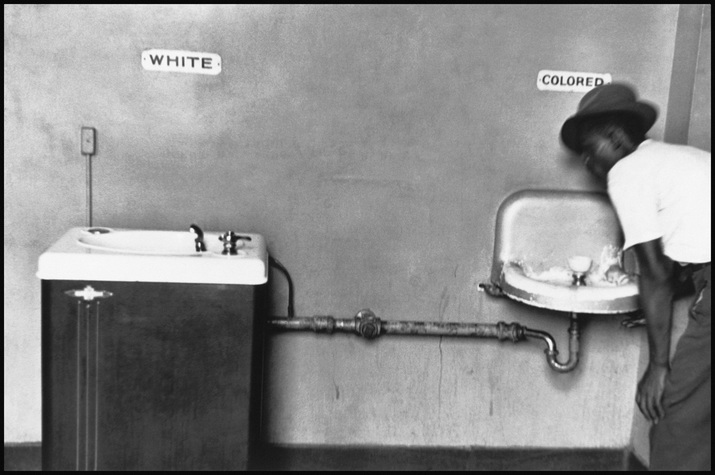

LUKE THOMAS Volume 10, Issue 6 Facebook tells me that on this day in 2014 I was in San Diego. I was staying there for a few days on a trip across the US to visit family. On this particular day, I was bored and a little hungover, so I just started walking. I walked through the touristy Gaslamp Quarter, past a group of dudes dressed as ninja turtles for Comic-Con, and then I somehow ended up in an abandoned parking lot full of makeshift shelters. There were dozens of people hiding from the sun under blankets or flattened pieces cardboard, or wandering aimlessly behind their shopping carts full of recyclable plastic bottles. It was surreal, especially since I had lived here as a kid and couldn’t connect these images with the America I thought I knew. Blacked-out police vans patrolled the area, intervening in one case when a man started street drinking at a gas station nearby. Seeing concentrated homelessness in your own backyard is extremely confronting, especially once I noticed that the wealth divide in the city was largely a racial divide. The week before, a teenager named Michael Brown was fatally shot by a police officer in Ferguson, MO, and I watched the riots from a TV at a local brewery later that night. They were the first of many shootings, protests, and riots that would happen across the US over the next two years, in Ferguson, Cleveland, Baltimore, New York, and most recently, Milwaukee. They were responses to police violence, failed community policing, and systemic oppression. What these cities have in common is a dividing line between the low socio-economic areas and the more privileged areas. Like San Diego, these dividing lines were often built by decades of race or class oppression. For example, according to 2010 census data, Milwaukee is the most segregated metro area in the nation, and any fan of The Wire has been introduced to the cyclical poverty and crime that came to define how people view black residents of Baltimore. These were forgotten suburbs, ignored communities with unaffordable housing, stagnant incomes, and underfunded public schools. De facto segregation in metropolitan areas is the visible representation of a wider problem. The San Diego parking lot was disproportionately full of black men. Consider this in light of the fact that while the African American population makes up around 7% of the total Californian population, black inmates make up nearly a third of the prison population (29%, according to 2013 CDCR data). In 2013, African American men in California were incarnated at nearly nine times the rate of the white population (4,367 black inmates per 100,000 members of the black population, as opposed to 488 per 100,000 for non-Latino whites). It’s clear that something is wrong on a structural level. As the poet Yusef Komunyakaa put it, ‘the cell block has replaced the auction block.’* But what does any of this have to do with Australia? According to a 2012 VicHealth survey of 755 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, 97% had experienced racism in the past 12 months and 44% reported being treated unfairly because of their race, ethnicity, culture or religion at least once a week. Racism isn’t just verbal abuse. It’s being locked out of the real estate or job market. It’s underrepresentation in politics and media and overrepresentation in prisons. Greg Howard noted in the NYT this week that the modern trend of defining racism as merely an individual character flaw has left us without a vocabulary to define systemic injustice, including the policies that created de facto segregation in the US. Racist acts are more often associated with slurs and tweets than disparate health and education outcomes. The redefinition of racism as a ‘problem of the heart’ halts progress and perpetuates substantively unjust policy-making because conflating racism with overtly racist comments does nothing to address the systematic injustice powered by racist sentiment, since ‘[s]ociety as a whole didn’t need reform for the sins of a few.’ That’s not to say that racist discourse doesn’t have its own role to play in reaffirming systemic injustice. Consider the xenophobic discourse leading up to Brexit, and then the subsequent explosion in hate crimes. Or consider our new senate members. As Amy McQuire, Michael Brull, and Samah Sabawi pointed out in New Matilda, what’s problematic about the resurgence of One Nation isn’t the content of their illogical, anti-factual arguments; rather, it’s the ‘imperceptible process of redefining our values’ that, throughout history, has followed this kind of discourse. One Nation may have fallen off the map for a while, but the repressive anti-immigration policies and brutal offshore detention regime that followed the rise of Hanson might not have been possible without One Nation’s influence in worsening our national discourse (see here). And as our political discourse keeps changing for the worse, we need to keep considering how our society is changing. Heaping shame on racist cartoons in the Australian or banana-wielding sports fans over social media is a singular response to a singular incident. Although it’s necessary to fight against these overtly racist sentiments in a way that demonstrates our inclusivity and commitment to human dignity, focusing on vilifying racist acts of individuals without having a larger conversation on systemic inequality excuses our own culpability in letting injustice exist. In the daily barrage of Hanson and Trump quotes, we need a renewed focus on ending systematic injustice before our voices get lost in the noise. Luke Thomas is a second-year JD student *Chris Hedges, ‘The World As It Is: Dispatches on the Myth of Human Progress’ (2012) The rest of this week's issue:

Comments are closed.

|

Archives

October 2022

|