|

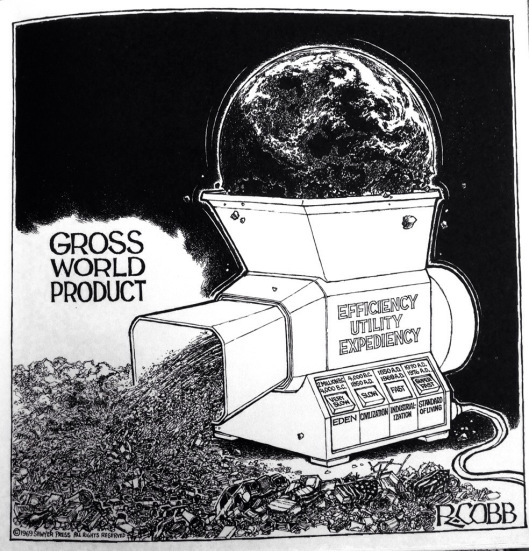

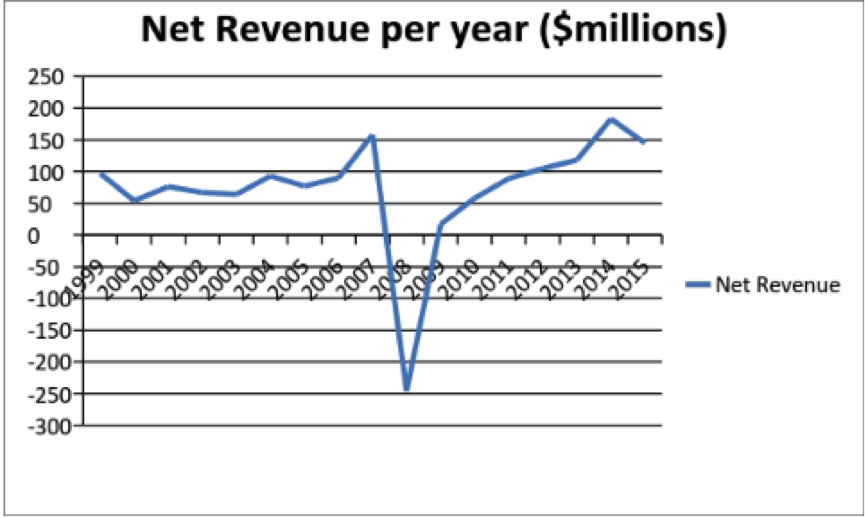

DUNCAN WALLACE Volume 10, Issue 1 On August the 8th, the University of Melbourne will release its draft Sustainability Plan, which will outline the tangible commitments the university is making to deliver a sustainable university. The university called for staff and students to “co-design the Plan”, stating that “this is your Plan and we need your help to advance the University’s sustainability performance and achieve its goals.” Staff and students responded in force, with 111 submissions made. The university has stated that “fossil fuel divestment and the University’s engagement with the sector as a whole was the main theme from responses.” It is unlikely that divestment from fossil fuels will be one of the commitments made, however, undermining the idea that the Sustainability Plan is “co-designed”. At just over $1 billion, the University of Melbourne endowment is the largest of any university in the country. Fossil Free Melbourne University (FFMU) for the past three years has been calling for the university to cease using this money to prop up the fossil fuel industry and to divest. This has been part of a global divestment movement which has seen institutions globally divest $3.4 trillion, including ANU, Stanford University and Oxford University. Through sustained activism, ranging from freedom of information requests, to a student referendum (97% of students voted in favour of divestment), to a naked rooftop protest, FFMU last month finally procured a meeting with Robert Johanson and Allan Tait, two key financial decision-makers on the University Council. Further, FFMU negotiated to ensure Johanson and Tait would be transparent regarding the barriers the university faces in committing to divest. At the meeting, the reasons that the university had so far refused to divest were finally laid bare. Previous arguments made by Vice-Chancellor Glyn Davis that what was holding the university back were the “likely lower returns” resulting from divestment were shown to be, at worst, lies and, at best, half-truths. FFMU reported the following: “We found out something we have suspected all along: concerns about the impact divestment will have on research funding, donations and scholarships money from the fossil fuel industry are stopping the University from standing with its students and divesting” (emphasis mine). The first thing to note is that the university is far from struggling financially. Earlier this month Standard & Poor’s affirmed its ‘AA+’ credit rating for the University of Melbourne, a credit rating two notches higher than the nation’s four banking behemoths (Westpac, NAB, CBA and ANZ). This is unsurprising – over the last 15 years Melbourne has averaged a yearly surplus of $73 million. *Note that figures include “impairment of available-for-sale financial assets”. The financial crisis in 2008 caused significant impairment. Figures do not, however, include increases in the value of available-for-sale financial assets.

But if the university has so much money, then why on earth is it risking human life on earth in order to retain research funding, donations and scholarships money from the fossil fuel industry? Shockingly, it appears that the reason is the desire to climb university rankings. Rankings, such as the Times Higher Education rankings, measure the opinions of business, of elite journals, and of international academics. The key to climbing rankings is to increase the amount of research published in top journals. As the university stated in its policy paper ‘Growing Esteem 2014’, “Lifting research performance and offering an outstanding learning experience brings visibility, global esteem and higher international rankings.” The University is already an excellent research institution. Nevertheless, the “ambitious goal for Melbourne” is to become a “billion dollar research enterprise by 2025” (here, p 30). The “significant additional income” necessary to achieve this goal will come from three areas: the philanthropy, partnerships with industry, and from teaching revenue. These three areas match almost perfectly the types of income cited as important streams of revenue from the fossil fuel industry. So there we have it: money from the fossil fuel industry will deliver the significant additional income necessary to fuel Melbourne’s climb up university rankings. But can this really be true? What about Glyn Davis’ argument that divestment will likely lower investment returns? It turns out that this is not what the evidence shows. Financial markets have priced into fossil fuel assets the assumption that all such assets will be dug up and burned. This is not possible a) because it will destroy the planet, and b) because governments have already committed to CO2 emission abatement which necessitates that only 1/5th of fossil fuel assets currently under management can actually be taken advantage of (see here, here and here). This “regulatory risk" will mean that these assets will become “stranded”, along with their value on the share market. This is exacerbated by the fact that, as the IMF recently showed, the mining industry simply would not be economically viable without global subsidies of $5.3 trillion a year - greater than the total health spending of all the world’s governments. Such subsidies are under threat from popular movements around the world pushing for renewable energy alternatives. It’s not a surprise then, to find that ethical investment funds have outperformed mainstream funds by more than 5 percent last year, and by more than 3% in the 10 years leading up to 2012. Glyn Davis’ argument simply does not stand up. And since the university is rich as it is and already an exceptional research institution, the only decipherable reason to chase money from the fossil fuel industry is to procure some of the “significant additional income” necessary for the irrational drive to climb university rankings tables. It should be noted that a focus on rankings is also bad for students. Warren Bebbington of Adelaide University has pointed out that rankings scarcely measure teaching or the campus experience at all. Indeed, “university rankings would have to be the worst consumer ratings in the retail market”. Phil Baty, editor of the Times Higher Education rankings, has said rankings should come with “health warnings”. Bruce Guthrie, a policy adviser at Graduate Careers Australia, says that “the only people who care about university rankings are vice-chancellors and the media". For other destructive effects of a focus on rankings see here. The arguments in favour of divestment are thus overwhelming. They show that when Vice-Chancellor Glyn Davis writes to you, as he did in 2014, and asks you “to share the University's excitement” at the news that the university has climbed some silly little rankings league, we should show great trepidation. Glyn Davis’ excitement is that of a madman, maniacally leading the way to the destruction of human life on earth. Duncan Wallace is a third year JD student and the Chief Editor of De Minimis. Duncan wrote this article in his personal capacity and it should not be taken to represent the views of the DM editorial team. The rest of this week's issue:

More articles like this: Comments are closed.

|

Archives

October 2022

|