|

DUNCAN WALLACE The University of Melbourne was created and is governed by Victorian statute. The preamble states that it is a “public-spirited institution with a mission that encompasses learning and teaching, research and knowledge transfer, all of which exist for public benefit.” Section 4 states that it consists of the Council, staff, graduates and students, and section 5 states that its object is to serve the local, national and international community by enriching cultural life, elevating public awareness of intellectual developments, and promoting critical and free inquiry. In section 8 it states that the University is governed by “The Council”, which has as one of its responsibilities and powers the appointment of the Vice-Chancellor - the chief executive officer of the University. Section 28 allows the Council to make the university statutes and regulations which constitute the internal law of the institution. Council membership consists of between 14 and 21 persons, of which at least 3 members must be elected under section 11(1)(d).

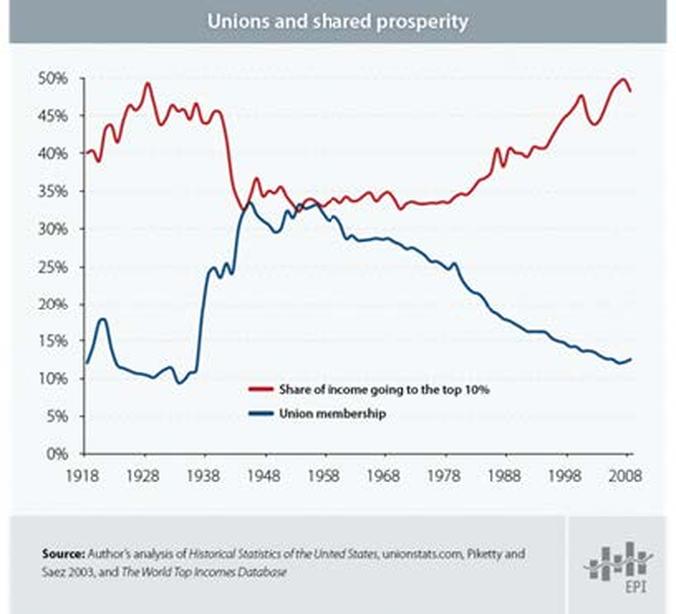

The university statute governing “Elections to Council” was repealed in June 2013, and the regulations governing election procedures were revoked in April 2013. It appears there are no more elected members on Council, and though the lawfulness of this is questionable, s 11(5) of the Victorian statute does state that “elected members” can be “elected or appointed” (emphasis mine), so perhaps its passable. As such, like the monarch under the Australian Constitution, the Council can be understood as a kind of rubber stamp. The real power lies with the Vice Chancellor, currently Glyn Davis, and the sub-strata of Faculty Deans, who for the law school is Professor Carolyn Evans. The Vice Chancellor “leads the development of University strategy and champions the discussion of strategic goals and new initiatives”, whilst the Deans are “accountable for the educational, research, financial and administrative performance of the faculty.” This small elite governs a community of more than 40,000 students and many thousands of staff, and has a budget of around $2 billion with which to do it. They reward themselves handsomely: Glyn Davis has a salary of around $1.2 million per annum. From publicly available documents it would appear that what motivates this elite is a kind of empire building. The University of Melbourne homepage, for example, currently has brandished across it a big “1”, underneath which is the slogan “it takes many to make history – Australia’s no. 1 university now ranked in the world’s top 50”. Similarly, in the law school “Welcome from the Dean”, Carolyn Evans boasts that “In the 2013 QS World Rankings of Universities by Discipline, we were ranked 5th best law school in the world and best in Australia and the Asia/Pacific region”. Various hangings around the law school proclaim the same. Fine, it’s nice to know you’re doing well. But what do these rankings actually measure? And what are those who hold power over the University prepared to sacrifice to keep climbing them? With regard to the first question, “QS”, cited by Carolyn Evans above, ranks universities based on “surveys of 70,000 academics and graduate employers, alongside measures of the impact of research”. The Times Higher Education (THE) rankings, mentioned numerous times recent University of Melbourne “Growing Esteem 2014” discussion paper, uses “13 carefully calibrated performance indicators” grouped into five areas: Teaching, Research, Citations, Industry income, and International outlook. But what does this all mean? Warren Bebbington of Adelaide University pointed out recently that the rankings scarcely measure teaching or the campus experience at all; indeed “University rankings would have to be the worst consumer ratings in the retail market”. Simon Marginson, formerly a professor at Melbourne, and who sits on the board of the THE rankings, has said the world would be a better place if rankings didn’t exist. "The link back to the real world”, he says, “is over-determined by indicator selection, weightings, poor survey returns and ignorant respondents, scaling decisions and surface fluctuation that is driven by small changes between almost equally ranked universities." Phil Baty, editor of the THE rankings, has said rankings should come with “health warnings”. Bruce Guthrie, a policy adviser at Graduate Careers Australia, says that “the only people who care about university rankings are vice-chancellors and the media". Rankings, therefore, do not measure student well-being. Nor do they measure the statutorily defined objects of the university – the serving of the community, the enrichment of cultural life, and the accommodation of free intellectual inquiry. Instead they measure the opinions of business, of elite journals, and of international academics. Which brings us to the second question: what are the management elite willing to sacrifice in order to satisfy their personal desires for high university rankings? Answers can be found in “Growing Esteem 2014”. One of the first things they are willing to sacrifice is their legal duty to promote free inquiry. Instead of free inquiry, the research direction of academics will be carefully monitored from above and their research output carefully measured against KPIs, one salient KPI naturally being university rankings. “Notwithstanding the University’s long-established research philosophy”, academics will now be understood as machines which produce papers, the quality of which is gauged by a select few journals. The University will accomplish this by “identifying a number of disciplines within each Faculty with the potential to be ranked in the THE World University Rankings top 20 and/or the ARWU top 40.” Ominously, “faculties unable to attain a top 20 or top 40 ranking” will have to be prepared to “make decisions around focus”, with academics given “clear guidelines on acceptable performance”. However to attain that kind of ranking, the research budget will need to be much larger. The “ambitious goal for Melbourne” is to become a “billion dollar research enterprise by 2025”. The “significant additional income” necessary to achieve this goal will come from three areas: the philanthropy of alumni, partnerships with industry, and from “teaching revenue”. The philanthropy of alumni will require a rich alumni. The University will therefore be focused on catering for those who are already well off, first, and second, it will be motivated to teach students skills useful for making money. A self-perpetuating elite will therefore be encouraged, and vocationally minded students will be found more and more difficult to accommodate. Partnerships with industry, which will provide “category 2-4 funding”, will be another branch of the attack on free-inquiry. It will “require some difficult choices for the academy — surrendering some control to be part of something wider”. It will be “important to explain better this new ‘engagement’ in which research is linked to relevant industry”, and the “challenge starts at home: the idea of ‘goal-directed research’ is challenging to many”, particularly in an “institutional culture [which] places a high premium on traditional research activities.” Finally, the way in which teaching revenue will be redirected is familiar to law students. This is done, firstly, by increasing fees by changing the ratio of undergraduate to graduate students. Five years ago, 72% of students were undergraduates; by 2015 the ratio will be 50:50. Since graduate fees are deregulated, the University can get more revenue per student. The second way is by cutting student services. The excellent coverage by De Minimis of the BIP has shown that the University will quite happily increase the costs to students’ health by making services more ‘efficient’, thereby freeing funds which are redirected to research. Ultimately, we must consider what kind of place we want the University of Melbourne to be. And, perhaps more importantly, we must consider who decides what kind of place the University of Melbourne is. Currently the people who decide are a corporatised management class, who operate within the paradigm of KPIs and centralised control. However running a community using KPIs does not work. Government emphasis on GDP has entailed an implicit commitment to eternal growth and environmental destruction; the concentration on private profits by banks created the implicit disregard for public loss – the systemic risk - which led to the financial crisis. University obsession with rankings is doing the same for intellectual freedom. It is no coincidence that attacks on their respective populations by the Australian government and by the University of Melbourne – in the budget and the BIP – have occurred at the same time. How democratic and inclusive civil institutions are has an impressive effect on how democratic and inclusive the country is. The graph below uses statistics from the US, but the statistics for Australia aren’t so different. Duncan Wallace is a 1st year JD student. This article was partly inspired by the first seminar on “How can we democratise the University?”, put on by the NTEU. A second seminar is on Tuesday 16th September 2014, John Medley Linkway at 12:30pm. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

October 2022

|