|

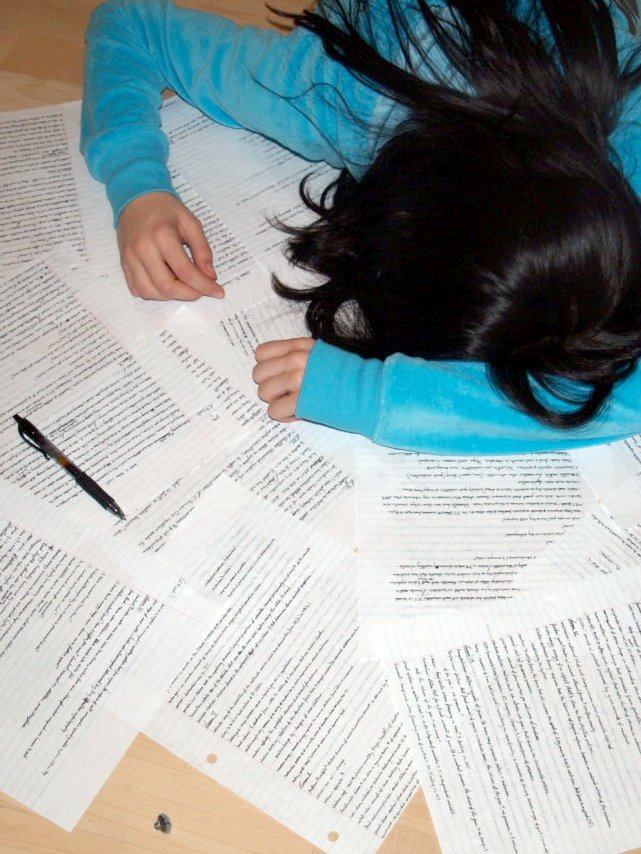

Vol 12, Issue 12 GEORDIE WILSON Assessments can be done better Gaining an approach to legal study that's fuelled by an independent interest in the law is important. Such a mindset can help push through the moments of boredom within the rewarding field of study. Another is more practical, those heading into the profession will need these habits for when there is a need to spend time outside of working hours keeping up competency in the law. As marks are perceived to be all-important by many, the approach many take to learning within this school is primarily driven by the assessment structure at MLS. Given that this is the case, formulating the structure of assessment is one of the highest impact decisions the administrators have upon our learning in the school. I think at one level this is recognised, and evident in the way that MLS conducts its assessment differently to most other law schools in Australia. However the system could be improved.

The standard unit assessment structure at MLS is the low-weight mid semester assessment and the high weight written exam. I’ve inferred these satisfy two respective goals in this place. The structure of the mid-semester as a low weight assessment serves as a way for student and lecturer to check if everything is on the rails at the semester mid-point. It's a low-risk point of feedback that carries marks so all try. The weighting of the final at MLS leads it to be an extremely stressful and high-risk way to assess competence of students throughout semester. Being so, why run assessments this way? Asking around, some lecturers indicated that high-weighted assessments are long-standing practice. However habitual practice only explains why this system hasn’t moved and doesn’t explain the motivations for this assessment structure in the first place. A search on Austlii or on Lexisnexis for orthodox law school methodology didn’t help either, and so we can only be left to guess. One motivation may have been to minimise the burden upon academics for assessment writing and marking throughout the semester. Another may have been an emulation of an Oxford model of assessment that values a minimisation of assessment throughout the semester in the hope that there is little disruption to the freeflow learning of students throughout. The second of these possible motivations is undermined by the necessity of a mid-semester assessment to compensate for the extreme format of the final assessments. The extreme weighting and limited time period for writing (typically 3 hours for 70% of a unit’s grade) means that these mid-semester checkpoints become very important. This spacing out has the effect, in an environment where marks are paramount, to require a dedication of focus toward upcoming assessments between weeks 3-7 of the semester. With only a short break before things begin to heat up again as SWOTVAC approaches. There isn’t much opportunity in the semester where the pressure is off for free form learning across the units. The do-or-die nature of the final exam also impacts upon the teaching of units and the way lectures are treated by students. With everything in semester leading towards a high-impact and high-risk exam meticulous detail is spent studying a lecturers preferences, and nuances toward a subject and relating those nuances toward how that interaction with the material should be interpreted with respect to a final exam, rather than an area of discipline. Teachers that have attempted to break this exam-focused pathology within the law school are often the least favoured among the students, as the construction of a speed-dial taxonomy that aligns with the mind of a lecturer is an effective way to approach the extremely time limited and high-stakes exams. With more than a frantic 3 hours to complete an assessment, there is more scope for a deep engagement with subjects than a panicked attempt at regurgitation. The need absorb these nuances from is a further distraction from independent learning within the subjects. So what are the alternatives? One could be a lowering of importance of the mid-semester assessment. By making all mid-semester assessments in this school ‘redeemable’, less focus need be paid to them and so the assessments would become much less disruptive throughout the semester. A poor outcome on a redeemable assessment would still serve the goal of serving as a litmus test before the final assessment, and so they could still have a healthy role to play. For the final assessments, the ability to take the assessments for a period longer than a mere 3 hours would allow for a less panicked and reactionary response to the course material. Deeper engagement with course material would be encouraged, and the potential to explore ‘rabbit-holes’ within topics, more realistic when such exploration won’t be made irrelevant or perhaps even too much of a risk to explore when time is so limited and assessments have such high stakes. A final assessment that consists of multiple components, such as a long-form essay alongside a hypothetical; perhaps stretched out over an entire weekend is clearly a better approach than the current default assessment structure within this law school, and it's an approach done before in a few units. Geordie Wilson is a second-year JD student and the Online Editor elect of De Minimis More articles like this: The rest of this issue (:O)

Jeremy Gans

17/10/2017 07:58:54 pm

What you've recommended (redeemable mid-semester, longer than 3 hours final, mux of essays and hypothetical) is the assessment for Crim. But, to say the least, student feedback in Crim is very mixed. Not all of that is the assessment, of course, but some of it is...

Author

17/10/2017 09:06:32 pm

Indeed the recommendation was made from that, reason being that after asking around students in higher grades the Crim assessment model was highly preferred. So i'm surprised to hear that the model of assessment is actually controversial.

Clare van Balen

18/10/2017 10:03:49 am

Based on conversations with peers, students are uneasy about the Crim exam because they don't know how to prepare for it. I suspect this has a lot to do with the subjects we do leading up to Crim. We are taught IRAC and checklists, but there is not a lot of skills-training until you get to Crim. Suddenly there's a different pedagogy and you feel like a fish out of water. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

October 2022

|