|

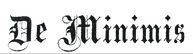

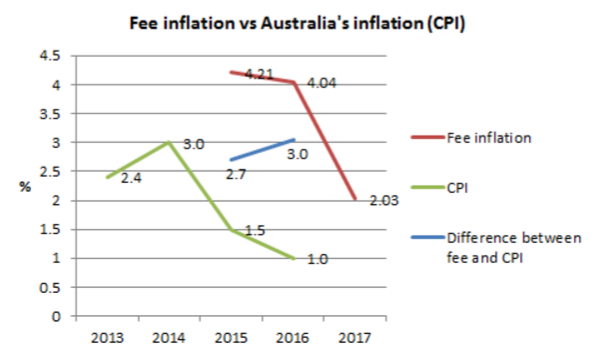

DUNCAN WALLACE Volume 10, Issue 11 A student contacted me last week to express the horror they felt when they looked at their statement of liability. Since 2014, the year they started the JD, fees for each subject (or ‘unit’) had gone up by $368. This meant that, compared to 2014, they were paying an extra $2944 per year if they did 8 subjects per year. Next year, fees for each subject will go up an extra $96. If they extend their degree by an extra semester, then, assuming they do three subjects, this would hit them with an extra $288 compared to if they’d finished ‘on time’. The student alleged that this was an unfair contract term under sections 23-28 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) – a term in a standard contract which can be varied unilaterally. This is unlikely, since, so far as I can tell, a contract is made for each subject and not for the course as a whole. Why each subject became individualised in this way is an interesting story with certain consequences, which will be gone into in a moment. And in fact, MLS is quite clear on this issue in its statement on fees on the MLS website: “The indicative cost of the standard three year program for students commencing in 2016 is $119,442. This is an estimate only that is provided to assist you in making your decisions and is based on a 5% rise in fees per year, which is higher than the average rise in recent years. The University guarantees that fees will not increase by more than 10% for subjects in any year.” Nevertheless, the concerns raised by my colleague are important. The Dean of the law school has at least a couple of times called the JD an “investment” (see here and here). But there is a problem with thinking of the JD as an investment. “Investments” are normally highly regulated. Chapter 6D of the Corporations Act, for instance, carefully regulates the manner in which corporations can fundraise. Prospective investors (unless they’re “sophisticated investors” (really rich people)), must be provided with disclosure statements. This is generally in the form of a “prospectus” (a full-disclosure document), though in some circumstances an offer of an “information statement” is enough. “Investments” in education, on the other hand, are hardly regulated at all. Despite the fact that students may be spending in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, no information is provided regarding the risk of this so-called investment. The key piece of information which prospective students would need when considering whether to “invest” or not is the grad-jobs statistics. These are not available, however, though the Dean has stated that “there is an argument for law schools collecting and sharing information about job outcomes with students who are entering degrees.” Further, risks are not adequately spelled out. Domestic students are often surprised to find out that they must come up with the $16k in cash which FEE-HELP won’t cover. A few weeks ago, for example, a student writing in De Minimis described their experience of having to get together $10,000. They did so by splitting it across two credit cards. Their advice to students considering the JD was first to speak to an accountant. Further, the fact that fees are now paid unit by unit, rather than for the degree as a whole, means that all the risk of failure is put on the shoulders of students and none is put on the university. Let’s say a student makes it through 1.5 years of the JD but has a mental breakdown and can’t go on. They now owe more than $50,000 and have nothing to show for it. This is particularly harsh on international students who don’t have access to FEE-HELP. Such students have to pay their fees up front, mostly without financial help from their government. To do so they have often scrambled together money from their parents and extended family. If they don’t make it through the JD, they and their families incur a massive loss. How universities came to charge per unit rather than for the whole degree began with the move towards university privatisation which was instituted by the Labor Government of the late 1980s. The higher education reforms of 1988 (the “Dawkins reforms”) allowed universities to charge fees for postgraduate courses. The concomitant decrease in government funding for universities caused Melbourne Law School, notably with some push back from faculty, to introduce a fee-paying program. Dean at the time Michael Crommelin has stated that this was “the only way we could acquire a little bit of space, a little bit of an opportunity to do anything else”. In particular, the increasing size of law firms meant that lawyers were moving from more generalised practitioners to specialists, particularly regarding commercial matters. Specialisation created a demand for specialist courses, which was being provided for by independent conference and seminar organisers. “High fees” were being charged and good profits being made. Cheryl Saunders has stated that “it occurred to us that if they were putting pots of money there, they might be able to put slightly smaller pots in our direction, as long as the product was a high quality one”. Note the commercial language thus introduced into education – it was becoming a “product”. Indeed, it was the Law School which pioneered at the University of Melbourne the use of consultants for market research. One of the first consultants engaged said that “the Law School lacks experience in being enterprising, market-responsive and competitive”. This soon changed – indeed, Cheryl Saunders helped the Law School win exemptions to the standard definitions of masters’ degrees and graduate diplomas from the university administration. The move to the JD from the LLB marked the culmination of this move – rather than subjects for specialists being taught on the side, the entire course was now one big profit-making enterprise. But the course was now split into 24 units as if each unit was a ‘subject-on-the-side’, rather than a holistic part of a law degree. This was how financial risk was shifted onto the shoulders of students, and, in fact, onto the shoulders of the general public. Student debt is expected to balloon to $63 billion by 2019, up from $30 billion last year, with a fifth of all loans not expected to be repaid. It is the government which will foot the bill. Universities are privatising profits and socialising costs. The risks to students are only going to increase. The gap between the proportion of fees which can be covered by FEE-HELP and the total cost of the course is growing. Rather than increasing fees at the inflation rate and so in line with the increase in FEE-HELP made available, the university is increasing fees at double the inflation rate. This will only serve to punish those who don’t have access to easy cash-flow from their parents. I show this in the following graph, though unfortunately I did not have access to enough data to compare more than two years directly: The Law School Dean invokes the “brand” of the University of Melbourne as what will mark MLS graduates out from other graduates in the job market. This brand she ties closely to how MLS is ranked in university rankings systems. Indeed, Melbourne’s ranking is often the piece of information students are advised to use to make their decision regarding their “investment”. As stated, however, by University of Adelaide Vice-Chancellor, Professor Warren Bebbington, “University rankings would have to be the worst consumer ratings in the retail market. In no other area are customers so badly served by consumer ratings as in the global student market”. “Next to buying a house”, he went on, “choosing a university education is, for most students, the largest financial commitment they will ever make. A degree costs more than a car, but if consumer advice for cars was this poor, there would be uproar”. I should be clear that the fault is not all that of the university. As mentioned, the Labor government of the late 1980s began the privatisation of the university sector. Now, Australian government funding of universities is the second lowest in the OECD: Governments across the OECD spent an average of 1.1 per cent of GDP on universities; Australia devoted just 0.7 per cent. Six countries – including Canada, at 1.6 per cent – spent at least double Australia’s proportion of national income. Finland, at 1.9 per cent, tops the list. It is government, therefore, and especially the Labor party (remember those videos of Joe Hockey protesting in favour of free education?), which is to blame for the corporatisation of universities. But corporatisation has been pushed from the inside as well. Corporatisation and an emphasis on profits tends to concentrate power in an elite at the top. We can see this in the huge salaries paid to university Vice-Chancellors: a headline from The Australian recently read, “Nine university vice-chancellors on more than $1m”. Melbourne’s Glyn Davis got $1.1 million last year. In June he also received, as a present from the University Council, more or less dictatorial powers as a result of University of Melbourne Statute changes. The concentration of power and wealth at the top has meant that, rather than fighting for increased public funding, Australia’s premier tertiary education institutions, in their own words, have “consistently supported the proposal for the deregulation of higher education fees as the only long term sustainable solution”. Admirably, our own Glyn Davis at one time tried to argue against this and in favour of higher public funding. He even “once argued for higher taxes on people like me so more Australians could access a quality university education”. The reaction he got, however, was “hostile, personal and visceral”, he says, and so he now simply enjoys his money and power without complaint. Perhaps this suggests that if we want to save our universities we will need to be a bit hostile and visceral (though “personal” may be too far). What I hope to have shown in the above, at least in part, is that an education is not something which should be privatised and commercialised. An education is a public good; it makes us into responsible citizens; it gives us the tools of intellectual self-defence; it allows us to question; to embark upon intellectual journeys. An education is not an “investment”. We cannot tell what a return on an education will be. Thinking of it as such will only prove to better serve the already well-off, shift risk onto students, and massively increase student stresses. It will make us into machines, there to mechanically do tasks without assessment of their merits and without question. That will be the only way for students to ensure a “return on investment”. In short, it will mean that we won’t be getting an education at all. Education must be free. To paraphrase Charlie Chaplin, we are not machines; we are not cattle; we are human beings. And we deserve to be treated as such. Unfortunately, it seems we’ll have to be a bit hostile if we’re going to convince our university’s Supreme Leader(s) of this. Duncan Wallace is a third-year JD student and Chief Editor of De Minimis. This article is written in his personal capacity. The rest of this week’s issue of De Minimis:

Tim Sarder

13/10/2016 08:01:05 am

"It is government, therefore, and especially the Labor party (remember those videos of Joe Hockey protesting in favour of free education?), which is to blame for the corporatisation of universities."

Anon

13/10/2016 04:27:22 pm

It's an attack upon Labor because the socialists feel betrayed by the Labor party's 1980s realisation that a socialist economic model doesn't work. This was demonstrated by Whitlam's disastrous economic policy generally, but specifically his changes to eductation, i.e. "free university" vs the Commonwealth's scholarship scheme.

Duncan

13/10/2016 10:00:06 pm

Lolol

Duncan

13/10/2016 09:59:29 pm

I wasn't attacking Labor specifically. I was nore pointing out that Labor and the Liberals have basically marginal differences. That was the point in invoking Hockey. What is key is getting both of them to move left. You can't really detach them policy-wise very far. I argue that point here: http://www.deminimis.com.au/home/unfair-budget-wont-even-fix-debt-problem

Education as a Many-Coloured Dreamcoat

13/10/2016 03:10:34 pm

Indeed, it is the myopic view of education as a mere economic investment that led to the Dawkins reforms and those since, with the demand-driven reforms a continuation of these. Education has value that cannot be quantified in the same way as any other financial investment, and it the sole focus on education as an investment that in the eyes of neoliberal governments, legitimises their approach, while in the eyes of people who think governments should do more to manage our society, is myopic. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

October 2022

|