|

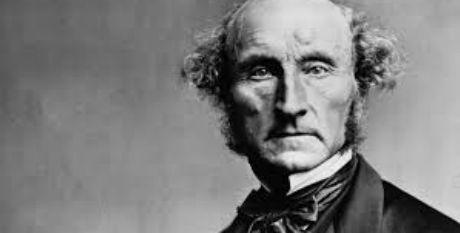

The greatest difficulty for Mill, the herculean task over which he labours here and throughout On Liberty, is to convince his readers to consider that they could, possibly, be wrong. In my view, the strongest of these arguments is what I will call the 'argument from accident.' To summarise:

Perhaps the argument carries little weight when applied to beliefs so absurd no-one has ever been recorded believing them, but where different communities have had radically different beliefs to our own, the argument is terrifyingly compelling. Prima facie at least, the community of our university generally reinforces the following beliefs: that prejudice against anyone on the basis of their race or gender identity is evil, that pleasurable sex between consenting adults is good, and that something like liberal democracy is the most desirable form of government. That slavery might be acceptable, that 'a woman's place is in the home', that sex outside of monogamous heterosexual marriage is somehow unethical, or that we'd be better off ruled by a dictator – these are thoughts that would rarely even reach the level of controversy on campus; they do not appear to us as serious possibilities. However, had we been born in first century Rome, we would have seen discrimination against women and slaves as simple common sense, had we been born in reformation England we would view 'deviant' sexuality as almost treasonous, and had we been born in feudal Japan democracy would have struck us as absurd. Our settled convictions, these thoughts which are, for us, impossible not to think, are simple accidents of history. It is no answer to point to our reasons, even our scientific authorities; most people convinced of their own tribe and times' values will be able to adduce good reasons in support of them. Ironically, On Liberty's age strengthens its case on this point. Mill's example of an unassailable, undisputed truth is 'the Newtonian philosophy'; through the early part of the following century general relativity and quantum mechanics combined to show Newton as being, if not quite incorrect, then at least radically incomplete. Empiricism is no guarantee of truth: the limits of Newton's equations were largely unobservable because the anomalies were largely to small or too fast. Mill had good, empirical reasons, (not to mention the consensus of all serious scientists) to hold up Newton as unassailably correct. And yet in this he was wrong. Good, empirical reasons and the consensus of authorities are no guarantee of our comfortable certainties any more than they were of his. The age of the text further serves to strengthen it in Mill's choice of the strongest opposing case: a belief in God and an afterlife. It was in defense of these beliefs, Mill felt, that his audience was least likely to be sympathetic to unrestricted freedom of expression: "To fight the battle on such ground gives a great advantage to an unfair antagonist; since he will be sure to say (and many who have no desire to be unfair will say it internally), Are these the doctrines [belief in God and an afterlife] which you do not deem sufficiently certain to be taken under the protection of law?" Mill's imaginary interlocutor echoes a popular objection against free speech in our own time: 'The only people who need the freedom to say racist things are racists.' It is rather shocking to read in Mill the assumption that his audience would view atheism as morally abhorrent as we view racism. And yet, apart from the accident of history that we are alive here and now, we might have felt the same. Ben Wilson is a third-year JD student More by Ben: The rest of this Issue: Comments are closed.

|

Archives

October 2022

|