|

TIMOTHY SARDER Volume 8, Issue 10 As expected, students at the law school are extremely savvy, politically astute and socially aware. The discussions in the floors at 185 Pelham St, the thoughtful pieces in the student magazines, and the deconstruction of intricate political issues I see on the JD Facebook pages, are a just a few instances where this is demonstrated. And I am proud to be amongst, and to engage with, such a community.

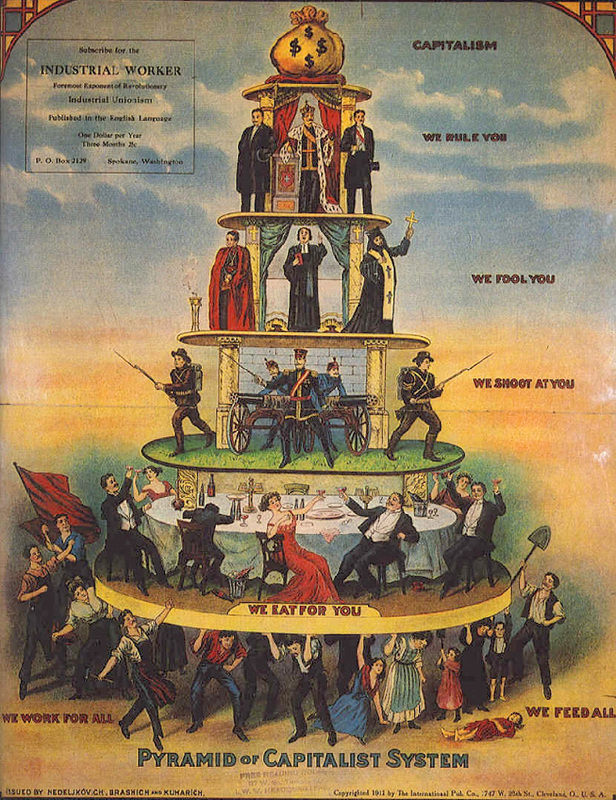

One that that talks about the issue of race, and gender equality. One that has publicly, through our LSS, representatives, recognised and advocated for the need for marriage equality. One that has Women’s Officers, and Equality Officers. One that takes discrimination of any kind seriously. But one thing we don’t talk about is class issues or material inequality. Or when we do, it’s often a strained or uncomfortable discussion. One that is quickly and unceremoniously dismissed. 2020 Presidential hopeful and husband to Kim Kardashian, Mr. Kanye West, has repeatedly stated “classism is the new racism”. Whatever you feel about this man, or whether a millionaire celebrity is entitled to lecture the public about class issues, there is something to this quote. It’s not that racism is disappearing or that classism is new – what has changed is that we are able to call out racism, but we can’t talk about class marginalisation. We don’t have the vocabulary and the discourse. Here at the law school, the problem is significantly more concentrated than it is in mainstream society. In addition to the abovementioned political backdrop, the personal experiences of students impede on meaningful discussion. A majority of the students here— myself included—experience or have experienced a certain amount of class privilege. Many of us were educated in private schools, live on campus at prestigious colleges or have parents who are happy to fund our studious lifestyles. But all of us take pride in the achievement of having got into the prestigious Melbourne Law School. Is it possible then that our hesitance to acknowledge class differentials— even in broad, apersonal terms— stems from a fear of acknowledging our own privilege and thus recognising that we didn’t achieve entrance to this course entirely on our own? That certain advantages helped us? Class difference doesn’t just help us get in. It makes a huge difference in the experience of the course itself. There’s a big difference in the experience of students are financially supported and/or well-off versus students who live independently, funded by Centrelink or the regular weekend shifts at a Sydney Rd cafe. The main difference is the time that comes with financial support. Students who don’t need to work to support themselves can afford to take unpaid legal experience and strengthen their CV – which is reflected in applicant outcomes for paid experience like internships or clerkships. The student who needs to work two to three days a week at Coles doesn’t have that luxury, and has less time to spend on readings, assessment and exam preparation – which is reflected in the bell curve For me, it’s often the difference between being able to study at night or feeling too exhausted from working a demanding hospitality job all day. It’s the difference college students get with private tutoring, or the ease of getting into university for classes. The point here isn’t to suggest resentment or “woe-is-me” cynicism, but only to say that the difference in class is real and marginalising, which is reinforced when we refuse to engage with it. I leave with a few suggestions that would make a start in addressing the abovementioned probems ; (1) making lecture recordings compulsory so the students with limited time or geographically disadvantaged have easier options; (2) more subsided options like textbooks for less affluent students (perhaps by improving the book fairy program); and a greater emphasis on helping students experiencing financial hardship acquire paid legal employment. But perhaps before these or other improvements will can implemented we first need to acknowledge that the difference exists. To recognise the advantages we have had in achieving success does not invalidate those achievements or ignore the hard work and talent involved in seeking them. But to not recognise them is to delude ourselves and marginalise others. When we’re comfortable in discussing so many other social issues, it is hypocritical to ignore this one. Let’s reflect on ourselves and broaden the discourse. Tim Sarder is a first year JD student

Tom

20/10/2015 11:16:25 pm

A salient point Tim - I think this would resonate with a lot of students from lower socio-economic backgrounds in the law school! Comments are closed.

|

Archives

October 2022

|