|

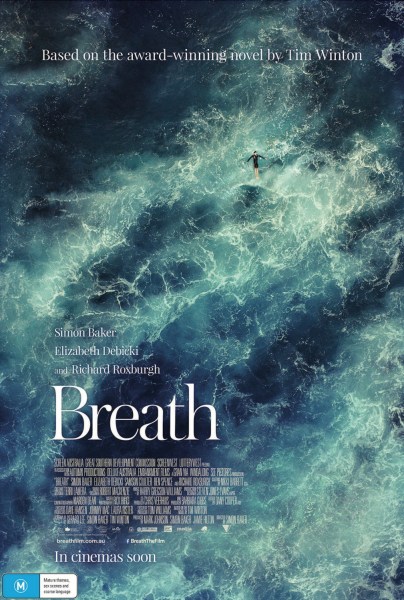

Issue 11, Semester 1 Film Review: Jacob Kairouz I thought that erotic asphyxiation couldn’t get more exciting, but I was wrong. The new film-adaptation of Tim Winton’s Breath had me seeing stars, but not for the reasons you might think. Winton has (rightly) pointed out that men are ‘shackled by misogyny’, so I went in assuming that his text would critique the gender binary. However, when I thought about the way gender is portrayed in the narrative, I realised that perhaps Winton himself is struggling to break free of his shackles. SPOILER ALERT: Breath is a story about two teenage boys, Pikelet and Loonie, who learn about the masculinity by competing to hold their breath underwater. They surf in dangerous conditions and risk drowning themselves with Sando, a surfer in his thirties whom they idolise as the pinnacle of masculinity. At the climax of the narrative, while Sando is away, Pikelet sleeps with Sando’s partner, Eva. But he soon realises that she only charmed him to convince him to play a game with her: she pulls out a plastic cellophane bag and asks him to help her ‘come like a freight train’.

The men in this story seem to fit neatly into the semiotic order, which Julia Kristeva describes as a feminine and emotional realm where the subject is at one with their environment and communicates non-verbally. Winton’s male protagonists certainly fit this description, holding their breath underwater and being unable to speak, like a baby in the womb. Their role model, Sando, says that surfing is about ‘your moment with the sea’. Pikelet even points out the femininity in surfing: ‘how strange it was to see men do something so beautiful… something pointless and elegant.’ However, this semiotic order is clearly riddled with masculine traits. Although the surfers are ultimately at the sea’s mercy, they nevertheless exercise agency over their actions. While Winton uses the semiotic to start a gender-critique, he doesn’t overthrow the gender binary, settling instead into Hemingway’s familiar man-versus-nature narrative. The apparent shackles of the gender binary are strengthened by Winton’s portrayal of his only female character. Eva reaches a state of semiotic bliss with a cellophane bag over her head, unable to communicate with words. While the men journey into the semiotic for a thrill in their fight against nature, Eva’s venture mixes danger with sexual pleasure. Before asking to be strangled during sex by a fourteen-year-old boy, Eva says how she misses ‘being scared’. I need only mention the tragedy of Louth v Diprose for us to recall how easily a woman’s sexuality is portrayed as villainous. But like our semiotic surfing heroes, Eva does have some agency: she is choosing to face the danger of suffocation, and she surely holds some power over a boy who’s half her age. Is this an empathetic portrayal of female sexuality, or is this the author’s fetishised misogynistic fantasy – strangling the sexual deviant who preys on vulnerable teenage boys? All I can say is that like so many authors before him, Winton ties masculinity to courage and power, while any power associated with femininity is tied to sex, death and the ecstatic. I can hardly blame him, he’s just performing his gender like everyone else. Interestingly, Winton blurs the definition of masculinity with respect to Pikelet, who returns to the semiotic in his sexual venture. In this one instance Pikelet struggles to live up to his masculine role. Winton links sexual pleasure to fear when this teenager feels obliged to strangle a grown woman in order to play his gender. We are all shackled to gender in a semiotic embrace, and we are all suffocating. We are helplessly forced under water in our battle to live up to societal expectations. This is certainly the battle that our protagonist, Pikelet, was facing. He was almost drowned trying to perform his gender, just as Eva might have wanted to suffocate to perform her’s. Instead of facing that sort of danger, perhaps we should be sensible and rise up against the gender binary who is clearly our common oppressor. We have nothing to lose but our chains. Until the world’s ready for that, I think I’ll just slink back to my bedroom, bring out the cellophane bag, read some more Judith Butler and think about how best to play my own gender. I’m so ecstatic I’m seeing stars already.

Cineasthetic

16/5/2018 07:06:29 am

The great Surfer cinema as masculinity deconstruction film has already been made - it's Kathryn Bigelow's Point Break. My favourite feminist film!

Oscar Daviews

18/5/2018 07:55:58 am

It's wrong of you to say that all men are shackled by misogyny. I'd be ashamed to think that I hate anyone. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

October 2022

|