|

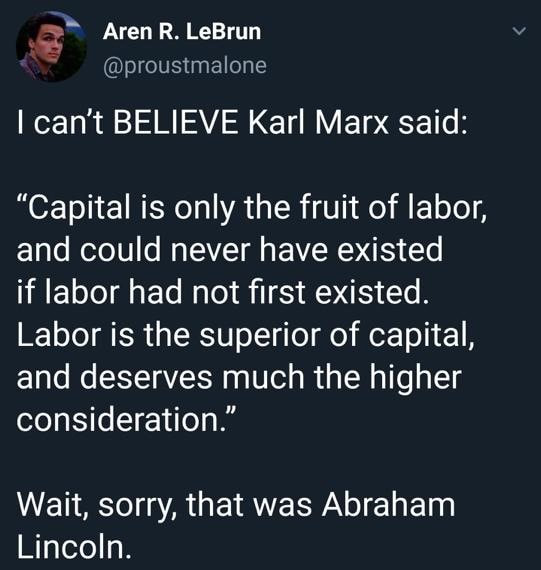

Issue 2, Volume 18 BREE BOOTH As the radical events of 2020 push people to the poles of the political spectrum (to use a somewhat inadequate analogy) political discourse is becoming less and less about producing just outcomes and more about one-upmanship. Relax, this is not really a political argument. No, this article attempts to bring to the reader’s attention some of the moral and hermeneutical challenges of engaging in debate in a world where information is too easy to come by, but where its validity has never been more suspect. Scrolling through social media one day, I came across a screencap of this tweet. Naturally, I decided to fact check this. It turns out that Lincoln did say this in his Message to Congress at its regular session on 3rd December 1861, in the midst of the American Civil War. So what’s the issue? It is accurate.

But is it really? Anyone vaguely familiar with 19th century political history can tell you that Marx and Lincoln had a very different message. When read in its context that quote is not an exaltation of the labouring proletariat but is steeped in classical liberal rhetoric about the ability of those who just ‘work hard’ to pull themselves up by the bootstraps. It raises very different political issues and appeals to very different underlying beliefs. The sentences immediately following those in the tweet read: “Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights. Nor is it denied that there is, and probably always will be, a relation between labour and capital, producing mutual benefits. The error is in assuming that the whole labour of the community exists within that relation… there is not of necessity any such thing as the free, hired labourer being fixed to that condition for life. Many independent men, everywhere in these States, a few years back in their lives were hired labourers. The prudent, penniless beginner in the world labours for wages a while, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land for himself, then labours on his own account another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him.” (Lest I be accused of taking this out of its context, I encourage readers to read the entirety of the speech which is to be found here. I include only this section for the sake of brevity.) The issue which this raises is a hermeneutical one, but it is also a moral one. Are we entitled to impute our own interpretation to the words of a speaker who, read in their context, cannot reasonably have been taken to mean that? This is an argument raised by both ends of the spectrum to attack the other: the accusation of “cherry-picking” evidence and statistics to suit their cause. In this era of big data and fake news, do we have an obligation to each other to represent our reality, meaning our own political views and intellectual histories, as honestly and accurately as possible? I’m not accusing the author of that tweet of deliberate or malicious fraud or misrepresentation. I myself am guilty of ‘pulling the rug out’ from under my unsuspecting friends with an out of context quote from Marx or Althusser. I accept that it was likely intended light-heartedly or as a joke. Even so, the joke works by the implication that Marx and Lincoln were closer to each other on questions of labour and capital than one might expect. This only works if the rest of both Lincoln and Marx’s political philosophies are pushed to one side. On its own, this kind of light-hearted misrepresentation arguably causes very little harm. However, there is a general trend in popular political debate of uncritical engagement with the words of theorists long dead. I would argue that honest and productive political discourse requires that we engage critically with our intellectual past. I further argue that this can only be done by considering what was really meant by these great thinkers, and that this kind of deep understanding cannot be had by throwing around out-of-context quotes in the midst of even light-hearted political debate. This is our moral and epistemological responsibility in a world where inaccurate information is too easy to come by. What I have said here is a jumping off point. I hope to have raised in this article some important philosophical questions about how we use knowledge and the purpose that it serves. I don’t purport to have given you the answers to these. My hope is merely that the reader will be inspired to consider their own answers to these questions as they continue to engage in our fraught political landscape. Bree Booth is a first year JD student.

What is

11/8/2020 08:24:34 pm

the point of this article?

Bree

11/8/2020 09:06:09 pm

Hi, original author here. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

October 2022

|