|

Vol 12, Issue 6 ELIF SEKERCIOGLU Caveat lector! The following contains plot details from The Neapolitan Quartet by Elena Ferrante. My friend Laura’s Dutch translation of L’amica geniale (‘My Brilliant Friend’) has a gold sticker on the cover. It proclaims the novel to be a bestseller and also, with no context, contains the phrase #ferrantefever. We laughed about this. Was it the password to a Dutch cult of Ferrante-loving Tweeters? Not many novels get their own official hashtag. Having already self-diagnosed with Italophilia sometime prior to choosing Italian as my undergrad major, I knew I had a lowered immunity to #ferrantefever. I succumbed. Strategically, I got my mother to read the first book and she was so enthralled that she purchased the remaining three for us.

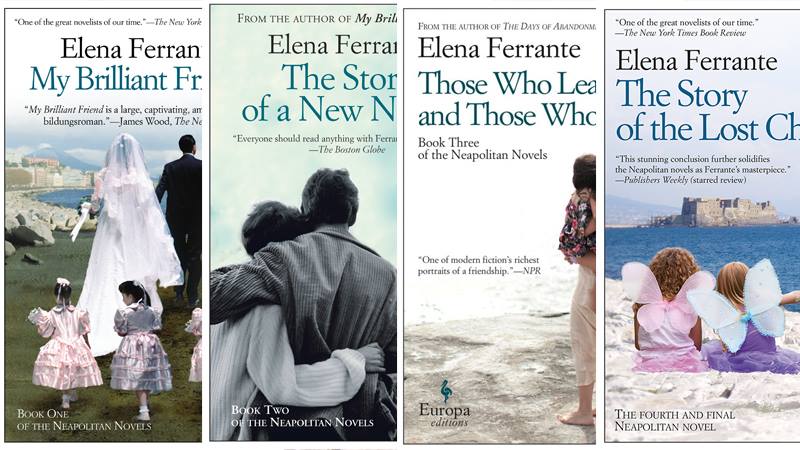

I am drawn to novels that follow the pattern of an intense childhood friendship between girls, a period of drifting apart and establishing separate identities and lives, and then a reunion, usually acrimonious, sometimes nostalgic. Emily Bitto’s The Strays is such a novel. Margaret Atwood’s Cat’s Eye is another. It is just as unsettling as her dystopian work like The Handmaid’s Tale. I remember particularly a moment in which the main character, who is bullied by her friends, peels strips of skin off the soles of her feet with disturbing calmness. The Neapolitan Quartet is also about how women can seize upon each other’s insecurities. It is four volumes, beginning with My Brilliant Friend, of what is essentially one novel. Elena, the narrator, charts the minutiae of her life from childhood to her 60s. The anchor of all this is her friendship with Lila, who lives in the same apartment. It is a relationship that over the course of many years will be wrought by jealousy, suspicions and power struggles. But they also understand and unconditionally love each other. The two women ‘get’ each other. This is part of the magic of a female friendship that is rarely seen in literature and film. Our setting is an impoverished corner of Naples. It is illiterate, violent and dirty. The poverty of this neighbourhood will indelibly stain Elena and Lila, they imagine others can see it as though they are clothed in it. Michele and Marcello Solara are the handsome young Mafiosi who run the ‘hood, busily heading up businesses in pastries, shoes and heroin. This isn’t Italy in the Eat Pray Love vein; there are no loving descriptions of fettucine gleaming sensuously in olive oil and pizza so thin the sun shines through it. Cooking in these novels is not for pleasure but just one of the menial household tasks women are expected to carry out uncomplainingly. I have been to Naples and by a coincidence was there with my own best friend since childhood. We were struck down by illness and spent our Neapolitan sojourn taking turns throwing up into the bin in our hotel room. The next day I heroically climbed Mount Vesuvius. The mysterious workings of memory and time have collapsed this into an interminable trudge through untouched snow, battling nausea. A quick squiz at my travel notes suggests that actually we had gotten a taxi most of the way up and I only walked the remaining 200 metres to the crater. Villages are built unsettlingly close to the foot of this volcano. Pliny the Younger would write about its eruption in 79 AD: ‘Many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness for evermore.’ Nearly two thousand years later, the fourth book is rent through by a violent earthquake. A true event, on November 23, 1980, it ripped through Southern Italy, leaving over 2,500 people dead and 250,000 homeless. Most of the aid money was never seen by the victims – billions went to the Camorra and corrupt politicians. A fitting symbol for a novel about corruption as the natural way of things. By the third and fourth novels Elena is in an unhappy marriage; she leaves her boring professor husband for the not-boring professor Nino, whom she has loved since she was a child. Even though Elena is narrating her own story, she cannot convince us that Nino is in any way redeemable. He holds court in gatherings of cultured people and exclaims progressive things like ‘a waste of a woman’s intelligence is the greatest waste of all’, whilst contributing nothing to housework and insidiously engaging in a gas lighting campaign that leaves our protagonist humiliated. The male characters are either terrible human beings, or they have no discernible personality. In contrast, the women are complex and surprising. Ferrante is unafraid of giving unlikeable qualities to her female characters. Elena and Lila are devoted to their children but don’t seem to particularly like them very much. You will get so into these novels that you will read them late into the night until your eyes tear up. You will blink out of your #ferrantefever and realise that you are not in fact trudging under a Neapolitan sun with the smudge of Mount Vesuvius in the horizon, but you are on the Mezzanine, and Remedies started half an hour ago. Elif Sekercioglu is a second-year JD student More Literary Lines: The rest of this issue: Comments are closed.

|

Archives

October 2022

|