|

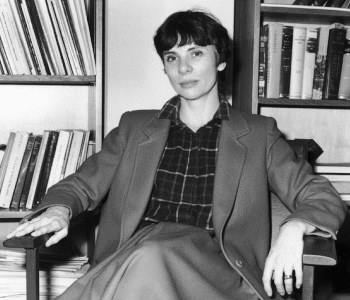

SARAH MOORHEAD Volume 10, Issue 5 Sarah Moorhead interviews our current MLS Judge in Residence, Justice Neave. Hi Justice Neave, thanks for agreeing to be interviewed for De Minimis, the law school’s -- Yes, I’m familiar with De Minimis — believe it or not, we had a De Minimis in my day, and it used to publish the most scurrilous… Ah, yes, well, I can assure it has changed its ways, it’s an upstanding publication nowadays, with not a blemish to its name… Moving right along, how did you get into law? Coincidentally! I’d never intended to do law — I wanted to do medicine — but then in year 11 I discovered that I found science much harder than the humanities, so I started thinking about Arts, and then Mum suggested law. I did very well in my first year of law — I liked the rational, logical argument side of law: my brain worked in that way. For a while, I saw that as the major thing I liked about law, but as I got more experienced, I saw the need to supplement the understandings from law with other disciplinary perspectives, and that’s when I got into law reform. Nowadays I think lawyers need lots of other skills as well. But yes, as an academic, I enjoyed the puzzle aspect so I taught conceptually difficult subjects like Property and Trusts. These other skills for a successful modern lawyer… pray tell? I’m very interested in the way law works on the ground, in the differences between the law as written and the law as practised. Lawyers need to be aware of the ways their practice, as well as the substance of the law, affects people. Changing the law is only a very small part of reform; it’s quite easy for lawyers to keep doing the same thing as always, even though the law has changed. Interesting; law people tend to assume — or at least, hope — that law reform is a solid path to social change…? Well, if you define ‘law reform’ broadly, to include procedure and practice, and the interactions of the law with other social forces, then yes, law reform can bring about real change. But one of the frustrations is that you can get the law right and nothing much changes: it needs to be complemented by changes to institutions that affect power inequalities. For example, once — a long time ago! — I thought that achieving formal equality for women would eventuate in substantive equality. Now we know that’s not true, and that we have to look at other elements of human existence that affect where people end up. There is, as you say, still a gap between the genders in terms of pay, seniority, etc. A lot has been written about it, most of it largely depressing for a female law student. Do you have any more positive messages? I’m blown away by the talents of young law students, particularly women. The real issue is how to reconcile having children (if you want to) with pursuing a career. The answer has to lie in family strategies and the participation of men in caretaking. I see some hope in the fact that men are taking a greater role in caring for children, but there is still a long way to go. The other thing you have to think about is what environment and areas you want to work in, and once you think beyond working for a large law firm (and some law firms are women-friendly now, but not all of them), there are other possibilities for combining really satisfying work with family responsibilities. Isn’t that coming close to putting the onus on women to find jobs that suit family responsibilities? Yes. Obviously we want to see structural change in society, but in the meantime… it’s a bit difficult to avoid that. It’s also very important for women to support each other. You headed an inquiry into prostitution in Victoria in the 80s, one of the recommendations of which was the decriminalisation of sex work. Tell us more? Believe it or not, the state government was worried about the planning aspects of illegal brothels — the sex work itself was illegal, but they were also very concerned about the breach of town planning regulations. I was asked to investigate how criminal laws and town planning laws among other things should change. The Inquiry made a range of recommendations, including that small businesses — one woman working alone, or with one other person — should not be subject to planning controls in the same way that other small business were, at the time, excepted. We interviewed sex workers, some users, looked at a lot of empirical data, and also did a lot of consultation. My ultimate view was that laws which punish sex workers do more harm than good, because the people who end up fined or in gaol are the women, not the men who use them. Sex work should not be normalised — advertising should not be allowed — but nor should we punish those involved in it, unless they’re forcing people into the industry against their will. Many of your recommendations were implemented, in stark contrast to, e.g., those of the Commission into Indigenous deaths in custody. Why? Luck, in part: in, for example, the Royal Commission into Family Violence, the government basically said they would implement our recommendations before we started! And it’s fair to say that the more complex the problem, the harder it is to bring about change. And of course after the initial attention gained through the media and so on, people lose attention and it’s hard to maintain political momentum. Community education is very important, to change attitudes. That takes time. But over my career, for example, when I started working there was no maternity leave for academics! I was involved in campaigning for that and for better childcare for students and academic staff and now these policies exist! So you’ve got to be patient, and take a long view, particularly with complex problems. On the topic of your career, you managed an extraordinary jump from academia straight to being an appellate judge, without having to be a barrister — please explain? I’d chaired the Victoria Law Reform Commission for five years; I think I was approached on that basis. I’d given a lot of speeches criticising the low number of women on the bench, so I suppose I was taken at my word! I was nervous, but I think I would have been more nervous if I’d been taking a trial judge position. Appellate judges deal with legal issues and legal argument — something I’d been doing for a long time. I also knew that I could make decisions. Some people are very good at legal argument, but find it hard to make the call. I knew I wouldn’t agonise too much. The other thing was that I knew I’d be sitting with other judges, so I was reassured insofar as I didn’t know very much about procedure — though that’s not outside the realm of human comprehension. It was partly luck, but also you have to be prepared to grab opportunities. You have to think, to make yourself think, “Oh yes, I can do this.” And then, you’ll find that you can! That is a truly lovely thing to hear as a third-year student faced with an array of career paths, all of which seem unobtainable, including the ones I don’t even think I want very much anyway. I think when you’re in your 20s, you agonise a lot about decisions that turn out not to matter all that much. I think a decision you make now probably won’t have as big an effect on your life as you think it will. You mean the subject I choose to fill my final elective won’t dictate my destiny?? The decision to clerk or not to clerk won’t open up or close forever the doorway to success?? It won’t! You’re going to live a long time! You’ll probably have 3-4 career changes within the law or outside it, and you’ll learn transferrable skills from all the experiences you have along the way, and that’s the way it should be — the days when you went to a firm and stayed there until you retired are gone, thank goodness. On the topic of future pathways, in honour of all those students in the grips of clerkship applications, I have one final question: tell us an interesting fact about yourself that we wouldn’t find out from your CV or cover letter? HAHAHA what a terrible question. Ahh, I would say I’ve had a very fortunate life and had lots of interesting and varied experiences, for which I’m very grateful. I feel like I could find that out from your CV… Well, I don’t have any strange hobbies if that’s what you’re after. Well, with my attempts at paparazzi journalism thwarted, do you have any final messages for the student body? Think broadly about what the law can enable you to do. When I think about people I studied with, or past students, and where they’ve ended up — they’ve had really diverse and interesting careers, and have taken opportunities that might have seemed a bit out of left field, which have opened up a whole world. So don’t be frightened! Don’t be too anxious! Sarah Moorhead is a third-year JD student The rest of this week's issue:Articles like this: Comments are closed.

|

Archives

October 2022

|